Table of Contents

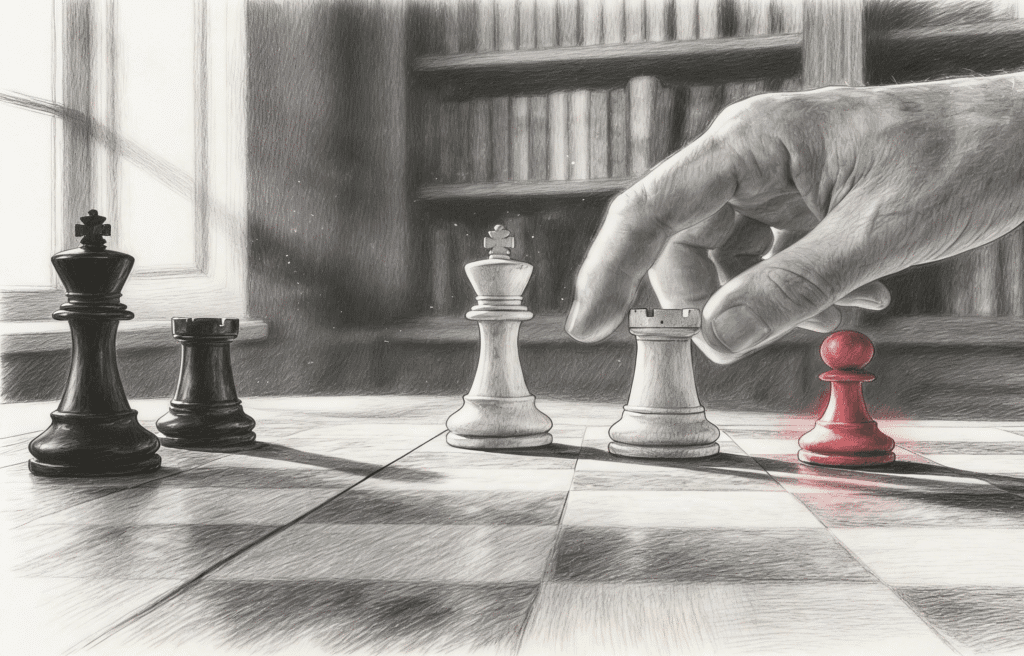

Endgame. Two kings standing face to face on an empty board, separated by a single square. Neither can move forward without stepping into danger. Neither can back down without losing ground. This frozen moment, this silent standoff, holds the secret to winning or drawing thousands of endgame positions. Chess players call it opposition, and understanding it transforms beginners into formidable endgame players.

The Invisible Force Field

Opposition sounds mystical, but the concept is beautifully simple. When two kings face each other with an odd number of squares between them, one king controls the confrontation. Think of it like two magnets repelling each other. The player who does not have the move holds the opposition. The player who must move faces an invisible force field that prevents penetration into key squares.

This matters because endgames strip away the complexity of the middlegame. No queens sweep across the board. No rooks defend distant files. No minor pieces create tactical threats. The endgame reveals chess in its purest form, where a single square decides between victory and defeat. And in this stripped down battlefield, opposition becomes the weapon that determines who controls those critical squares.

The beauty of opposition lies in its universal application. Whether fighting a king and pawn endgame or maneuvering in a rook endgame, the principle remains constant. Control opposition, control the outcome.

Why One Square Changes Everything

Chess rewards precision. A tempo lost, a square abandoned, a king misplaced by one file can flip the evaluation from winning to drawn or drawn to losing. Opposition captures this precision in its essence.

Consider a fundamental scenario. White has a pawn racing toward promotion. Black’s king tries to stop it. If Black’s king can reach certain key squares before the pawn, the position draws. If not, White wins. Opposition determines who reaches those squares first.

The player with opposition forces the opponent’s king backward or sideways, never forward. This creates a zugzwang situation, that wonderful German word that means “compulsion to move.” The opponent must move but every move worsens their position. In endgames, zugzwang appears constantly, and opposition often creates it.

Think of opposition as chess real estate. The player holding it owns the valuable property. The opponent must watch helplessly as their position deteriorates with each forced move.

The Three Faces of Opposition

Opposition appears in three distinct forms, each serving different strategic purposes. Direct opposition seems obvious once explained. The kings face each other on the same file, rank, or diagonal with one square between them. Picture two heavyweight boxers touching gloves before a fight, neither giving ground.

Distant opposition extends this concept across the board. The kings might stand three or five squares apart on the same file, rank, or diagonal. The number must be odd. This long range version matters when both kings race toward a target. The player with distant opposition will arrive at the critical squares with opposition when the kings finally meet.

Diagonal opposition adds another layer. The kings stand on the same diagonal separated by an odd number of squares. This form proves crucial when the battlefield spans both horizontal and vertical planes. A king approaching from the side often needs diagonal opposition to penetrate enemy territory.

Understanding all three forms elevates a player’s endgame vision. Suddenly, the board reveals hidden connections. A king five squares away actually controls the opponent’s king. Space and distance bend to the will of opposition.

The Pawn’s Best Friend

Pawns dream of promotion, but they need protection during their journey. A lone pawn facing an enemy king usually draws because the defending king blockades the pawn or captures it. Add a friendly king to escort the pawn, and everything changes. Opposition decides whether the pawn promotes or dies trying.

The escorting king must shield the pawn from the defending king. When the defending king tries to approach, the attacking king takes opposition and forces it away. When the attacking king advances with the pawn, it must maintain opposition to prevent the defending king from reaching blockading squares.

This dance between the three pieces, two kings and one pawn, creates some of chess’s most elegant patterns. The geometry feels mathematical yet artistic. Square color matters. Pawn position matters. King placement matters. Opposition ties these elements together into a coherent strategy.

Players who master opposition in king and pawn endgames gain two moves ahead of their opponents. While the opponent calculates variations desperately, the player with opposition knowledge sees the result immediately. This psychological advantage compounds the technical advantage.

When the Board Empties

Many games reach positions where material diminishes to kings and pawns. Tournament players know these endgames decide half their results. Club players often misplay these positions, missing wins or failing to hold draws. The culprit? Misunderstanding opposition.

The critical moment arrives when both sides have equal pawn structures or when one side holds a single extra pawn. Textbooks analyze these positions endlessly, but they all revolve around the same principle. The side with opposition at the crucial moment wins or draws depending on the material balance.

Picture a position with pawns locked across the center. Neither side can advance pawns without losing them. Victory requires a king breakthrough on one flank. The player who gains opposition on that flank breaks through. The opponent’s king gets pushed aside, unable to defend the pawns behind it.

This explains why strong players value tempos in the endgame. A spare pawn move, a king triangulation, an extra square available for maneuvering, all these factors help gain opposition at the decisive moment. Endgame mastery means calculating not just king positions but opposition relationships across multiple moves.

The Square of the Pawn

Opposition connects deeply with another endgame concept called the square rule. When a pawn races to promotion against a lone king, a simple rule determines the result. Draw an imaginary square from the pawn to its promotion square and extend it sideways. If the defending king can enter this square on its turn, it catches the pawn. If not, the pawn promotes.

But what happens when the attacking king escorts the pawn? The square rule alone cannot answer this question. Opposition must join the calculation. The attacking king uses opposition to shrink the defending king’s square, preventing it from entering. The defending king needs opposition to expand its reach and enter the square.

These two concepts, opposition and the square rule, work as partners. Together they solve nearly every king and pawn endgame. Separately, each has limitations. Understanding their relationship transforms abstract knowledge into practical winning technique.

Learning to See What Others Miss

Beginners overlook opposition entirely. They move kings randomly, hoping to somehow capture pawns or promote their own. Intermediate players know opposition exists but apply it inconsistently. Advanced players see opposition relationships instinctively, like a musician hearing chord progressions.

This progression requires training the eye to see patterns. When examining any endgame position, strong players ask: “Who has the opposition?” before calculating specific moves. This question focuses attention on what matters most.

Training means studying classic positions. The Lucena position, the Philidor position, key squares in pawn endgames, all these standard patterns teach opposition through repetition. Study enough examples and the brain starts recognizing the patterns automatically.

Practical play reinforces theoretical knowledge. Playing out endgame positions against other players or computer programs builds intuition. Mistakes in these practice sessions cost nothing but teach everything. The king that could have taken opposition but moved to the wrong square, the pawn push that surrendered opposition, these errors burn lessons into memory.

Opposition succeeds because chess operates on geometric principles. The king moves one square in any direction. This simple movement creates complex spatial relationships. Opposition exploits these relationships by controlling key squares through king placement.

This geometric reality makes opposition objective and calculable. Unlike strategic concepts that involve judgment calls, opposition either exists or does not exist. The kings either face each other correctly or they do not. This objectivity makes opposition reliable. Master it once and it works in every game forever.

The principle extends beyond pure king and pawn endgames. Rook endgames, bishop endgames, knight endgames, all benefit from understanding opposition. Even positions with queens on the board sometimes reduce to opposition battles. The player who recognizes these moments gains a decisive advantage.

Common Mistakes and Missed Opportunities

Players lose drawn positions and draw won positions by mishandling opposition. The most common mistake involves moving the king when waiting moves exist. The opponent has the opposition and forces the player to move. Instead of maintaining position, the player advances and loses control.

Another frequent error occurs when players focus entirely on attacking enemy pawns while ignoring opposition. They maneuver their king toward a weak pawn but arrive with the wrong opposition relationship. The defending king simply blocks, and the attack fails.

Premature pawn moves also surrender opposition. Players push pawns to create threats but sacrifice the flexibility needed to maintain opposition. The opponent’s king marches forward unopposed and breaks through.

Perhaps the subtlest mistake involves failing to preserve distant opposition. Players correctly fight for direct opposition in front of pawns but forget about distant opposition earlier in the game. They allow the opponent’s king to improve its position five squares away, and when the kings finally meet, the opponent already controls the confrontation.

Building Intuition Through Patterns

Chess improvement happens through pattern recognition. The brain stores thousands of positions and their evaluations. When a similar position appears in a game, the brain retrieves the stored pattern and applies its lessons. Opposition works the same way.

Start by memorizing simple positions. White king on e4, white pawn on e5, black king on e6. Black has the opposition and draws. Change the black king to e7, and White has the opposition and wins. Drill these basic positions until recognition becomes instant.

Then add complexity. Two pawns per side. Pawns on different files. Pawns blocked against each other. Each variation teaches new lessons about opposition. The brain gradually builds a library of patterns.

Eventually, examining a new endgame position triggers pattern matching. The mind thinks: “This looks like that position I studied. The same opposition relationship exists. Therefore, the result should be similar.” This intuitive leap, from pattern recognition to evaluation, marks true endgame mastery.

Theory means nothing without application. Take opposition knowledge into actual games. When the board simplifies to an endgame, pause and evaluate opposition. Ask: “Who would benefit from having the move right now?” If the opponent benefits, maintain position or triangulate. If you benefit, advance carefully while preserving opposition.

Calculate variations by checking opposition at each critical moment. Before pushing a pawn, verify the resulting position. Will you retain opposition? If not, can you regain it? If neither, perhaps pushing the pawn surrenders the advantage.

Watch opponents struggle against opposition. Players unfamiliar with the concept make predictable mistakes. They advance when they should wait. They wait when they should advance. They move their king to wrong squares repeatedly. Exploit these errors mercilessly while learning from them for your own games.

Opposition deserves study because it delivers results. Learning the theory takes hours. Mastering the practice takes longer but pays dividends in every endgame thereafter. Players who understand opposition convert more advantages into wins. They save more inferior positions into draws.

They navigate endgames with confidence instead of anxiety.

Pingback: Chess Endgame Refresher: K+P vs K - chessheritage.com

Pingback: Why Your Next Promotion Might Depend on Your Chess "Endgame" Strategy