Table of Contents

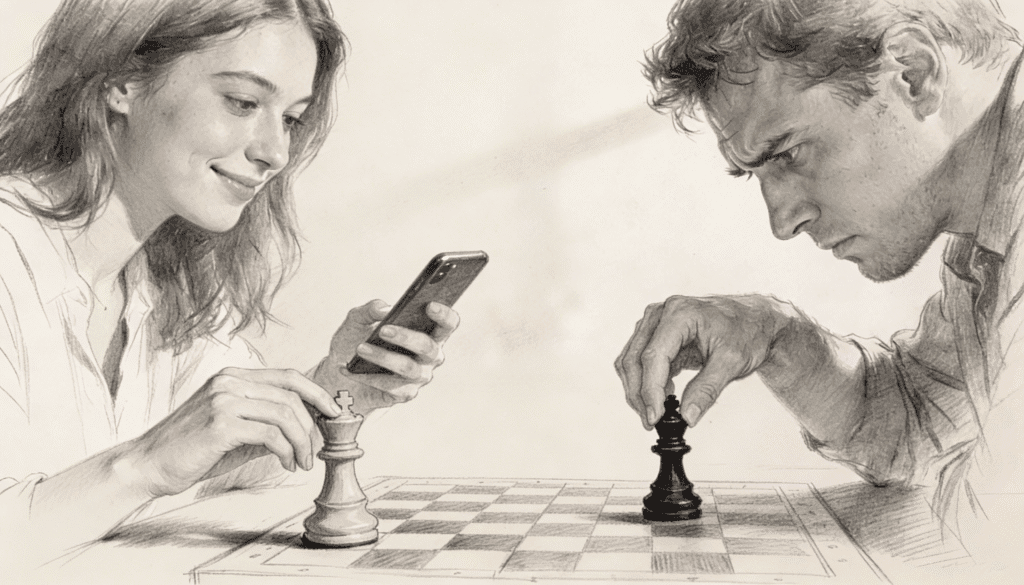

The corporate executive sits down at the chess board with confidence. Between moves, she glances at her phone. A quick text here, a calendar check there. She prides herself on handling twelve things at once. Twenty minutes later, she stares at the board in confusion. Her queen hangs undefended. Her king stands exposed. The position that seemed manageable now resembles a car accident in slow motion.

This scene plays out in chess clubs and online platforms every day. The people who excel at juggling tasks in their daily lives often crumble when facing the checkered battlefield. The pattern reveals something uncomfortable about how modern brains work, or perhaps more accurately, how they pretend to work.

The Illusion of Parallel Processing

The human brain operates like a single spotlight in a dark theater. It can only illuminate one actor at a time. When someone claims to multitask, they’re actually switching that spotlight rapidly between different performers. Each switch costs something. The brain needs time to remember where it left off, to rebuild context, to figure out what matters next.

Research from Stanford University found that chronic multitaskers perform worse than focused individuals at every measure of cognitive control. They struggle to filter out irrelevant information. They take longer to switch between tasks. Most surprisingly, they even perform worse at multitasking itself compared to people who typically focus on one thing at a time.

Chess makes this reality brutally visible. The game offers no place to hide.

Where the Walls Close In

A chess position contains around 40 legal moves on average. But the real complexity lives deeper. Each move creates a new position with its own 40 possibilities. Think three moves ahead and the mind must evaluate not just moves, but trees of moves, forests of consequences spreading in every direction.

The multitasker approaches this with a fragmented attention span. She calculates one line of play, gets distracted, then returns to calculate a different line. The first calculation has faded. The connections between variations blur. What she thinks she analyzed might be a ghost memory, a false confidence built on incomplete work.

Meanwhile, her opponent sits in unbroken concentration. He doesn’t have more raw intelligence. He simply maintains an undivided focus. His mental spotlight stays pointed at the board, and only the board. The contrast in results speaks for itself.

The Pattern Recognition Problem

Strong chess players don’t calculate everything from scratch. They recognize patterns the way a reader recognizes words without sounding out individual letters. A grandmaster glances at a position and sees familiar structures: a weak king, an overextended pawn chain, a knight that controls key squares.

This recognition happens in the quiet spaces of sustained attention. The pattern emerges when the mind stays still long enough to notice it. Multitaskers never reach this depth. They skim the surface, catch the obvious pieces, but miss the subtle arrangements that define a position.

Consider how a musician learns a complex piece. The notes must be played hundreds of times, with full attention, before they become automatic. The same applies to chess patterns. They embed themselves through repeated, focused exposure. Switch attention away too often and the patterns remain forever foreign, forever requiring conscious effort to decode.

The False Economy of Time

Multitaskers often justify their approach with efficiency arguments. Why stare at the board for five minutes when you could answer three emails and still make a decent move? The logic seems reasonable until the game is lost.

Chess rewards depth over speed. A player who spends thirty minutes on one critical decision often outperforms someone who makes fifteen moves in the same time. The quality of thought matters more than its quantity. One brilliant insight, born from sustained reflection, can transform an entire game.

The multitasker optimizes for the wrong metric. She counts tasks completed rather than problems solved. In chess, as in many difficult endeavors, the scoreboard only shows wins and losses. How busy you looked while losing counts for nothing.

Chess makes this principle crystal clear because the feedback arrives quickly. Play with divided attention and you lose, often within an hour. No ambiguity, no excuses, no way to blame external factors. The board tells the truth.

The Deeper Revelation

The multitasker’s failure at chess illuminates something beyond games. Modern life celebrates busy people. Calendars packed with meetings signal importance. Responding to emails within minutes suggests dedication. The person juggling five projects simultaneously appears more valuable than someone working deeply on one.

But what if this entire framework rests on a mistake? What if the appearance of productivity has become confused with actual accomplishment?

Cal Newport, a computer science professor and author, argues that the ability to perform deep work has become increasingly rare and therefore increasingly valuable. While everyone else fragments their attention across dozens of inputs, the person who can still think deeply about complex problems has a significant advantage.

Chess serves as a laboratory for testing this hypothesis. Remove all distractions, demand real cognitive effort, and see what happens. The results suggest that society might be optimizing for the wrong things.

The Cost of Context Switching

Every time attention shifts, the brain pays a tax. Researchers call this “attention residue.” Part of the mind remains stuck on the previous task, even after shifting to something new. The effect compounds with repeated switches.

In chess, attention residue creates phantom fears and missed opportunities. A player glances at her phone to check a notification. She returns to the board, but part of her mind still processes that notification. She overlooks a tactical blow because her mental resources aren’t fully allocated to the position. The game punishes this inefficiency without mercy.

The same dynamic plays out in supposedly productive multitasking. The executive who switches between a strategy document and email every five minutes never achieves full immersion in either task. The quality of both outputs suffers, though the busy feeling creates an illusion of achievement.

Training the Opposite Muscle

Learning to play chess well requires developing a skill that modern life actively discourages: the ability to sit with one thing for extended periods. No switching. No relief from difficulty. Just sustained engagement with a single complex problem.

This feels uncomfortable at first, almost physically painful. The urge to check something else, to introduce variety, to escape the cognitive strain becomes nearly overwhelming. Push through that discomfort and something shifts. The mind settles. Deeper patterns become visible. Solutions that seemed impossible start to emerge.

The Choice Facing Everyone

The chess board offers a clear choice. Approach it with divided attention and fail. Approach it with focus and have a chance at success. Life rarely presents such obvious feedback, which makes the lesson easy to ignore.

But the principle holds whether or not the feedback arrives quickly. The writer who checks social media every ten minutes produces shallower work than the writer who disconnects for three hours. The programmer who keeps twelve browser tabs open writes buggier code than the programmer who closes everything unrelated. The difference just takes longer to become obvious.

The multitasker’s failure at chess should serve as a warning. Not that everyone needs to play chess, but that the skills chess requires matter deeply. The ability to think about one thing completely. The willingness to sit with difficulty without seeking escape. The patience to let understanding develop rather than forcing quick conclusions.

These capacities seem old fashioned in a world of instant messages and infinite streams of content. Yet they remain essential for any work that actually matters. Chess hasn’t changed in five hundred years. The truth it reveals about human cognition hasn’t changed either.