Table of Contents

The board is set. Two players sit across from each other, identical pieces arranged in perfect symmetry. One will win, one will lose. But here’s the twist that separates chess from almost every other competition: winning isn’t about having better pieces. Both sides start with exactly the same army. Victory belongs to whoever understands that the game isn’t really about the pieces at all.

This reveals something profound about advancement, whether on the chessboard or in a career. The player who focuses solely on protecting their pieces and executing their immediate tasks flawlessly will lose to the player who sees the bigger picture. Every single time.

The Trap of Excellence

Consider the player who develops their pieces beautifully. Knights find perfect outposts. Bishops command long diagonals. The rooks double on an open file with textbook precision. Each piece does exactly what it’s supposed to do. This player might spend the entire game congratulating themselves on their fine technique.

Meanwhile, their opponent has been doing something entirely different. Sure, their pieces might not occupy the most aesthetically pleasing squares. But they’ve been building toward something. A weakness in the enemy position. A square that can’t be defended. A king that will soon have nowhere to run.

The first player was doing their job. The second player was winning the game.

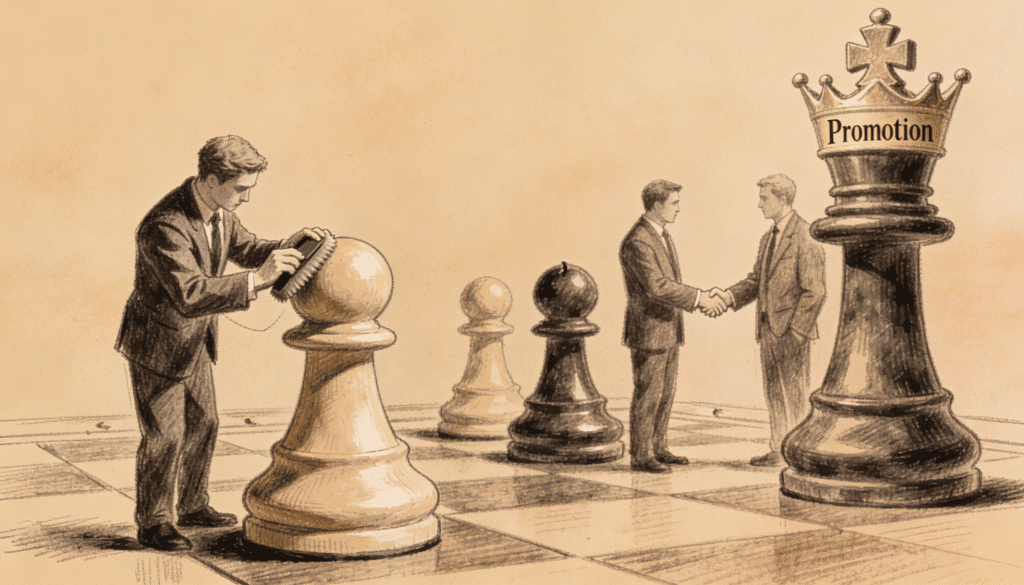

This is the promotion paradox in its purest form. The paradox states that the skills that make you excellent at your current level often have surprisingly little overlap with the skills needed at the next level. The reliable knight that controls key squares might be perfect for that role, but promotion to a queen requires a completely different kind of thinking.

What the Board Actually Rewards

Chess has a dirty secret that beginners discover painfully: the game doesn’t care about fairness. It doesn’t reward you for developing all your pieces evenly. It doesn’t give you points for making sensible, solid moves. The only thing that matters is the result.

A player can make twenty brilliant moves and one terrible blunder, and that single mistake will define the entire game. Another player can drift for nineteen moves, playing nothing special, but seize the one critical moment that matters. Guess who wins?

The evaluation isn’t based on average performance. It’s based on whether you delivered when the position demanded it.

This creates an uncomfortable truth. The player who focuses on “doing everything right” is optimizing for the wrong metric. They’re like someone trying to get promoted by having perfect attendance and always hitting reply within two minutes. These things might be necessary, but they’re not sufficient. They’re not even close.

The Architecture of Advancement

Strong players understand that chess operates on multiple levels simultaneously. There’s the level of individual pieces and their immediate safety. Then there’s the level of pawn structure and space. Above that, strategic plans and long-term advantages. And at the highest level, an understanding of what the position actually requires.

Most players get stuck because they confuse competence at one level with readiness for the next. They’ve mastered the art of keeping their pieces coordinated and protected. Excellent. But the next level isn’t about better coordination. It’s about understanding when to abandon coordination entirely in pursuit of something more valuable.

The same pattern appears everywhere. The person who gets promoted isn’t usually the one who does their current job best. It’s the person who demonstrates they understand the job above them. They’re already thinking about problems at that level, even while technically operating below it.

The Visibility Problem

Here’s where chess gets especially instructive. When a master plays, their most important moves often look quiet to weaker players. The master plays a seemingly modest pawn push, and spectators wonder why everyone’s excited. Three moves later, the position has transformed. That unremarkable pawn move created the conditions for everything that followed.

The spectacular sacrifice that wins the game? That gets attention. But the preparation that made the sacrifice possible? Invisible to most observers.

This creates a genuine problem for advancement. The work that actually matters at higher levels often doesn’t look impressive to people operating at lower levels. The person evaluating you for promotion might not even recognize your most valuable contributions because they’re outside their frame of reference.

In chess terms, you might be playing master-level prophylaxis, preventing your opponent’s plans before they even form. But if your opponent isn’t strong enough to have had those plans in the first place, your prevention looks like nothing happened. You get no credit for problems you solved before they existed.

Building Coalition Power

No piece promotes alone. This is literally true in chess, where a pawn’s journey to the eighth rank requires support, protection, and often sacrifice from other pieces. But it’s metaphorically true about advancement in general.

The queen is the strongest piece, but it can’t operate without help. Place a queen on an empty board against a king, and it can’t force checkmate. It needs support. The most powerful piece in the game requires the lowliest pawn to accomplish its ultimate goal.

This is where many talented individuals fail. They develop personal excellence but not coalitional power. They can execute brilliantly in isolation but haven’t built the network of support that makes advancement possible.

Watch how strong players use their pieces. The bishop isn’t just controlling squares for its own sake. It’s supporting a future knight maneuver. The rook isn’t just occupying a file. It’s preparing to invade while the bishops keep the enemy pieces at bay. Every piece functions as part of a larger system.

Advancement requires constructing this kind of mutual support. It means making other people more effective. It means creating situations where your success and their success become linked. The player who hoards material and refuses to trade pieces often ends up with a technically superior position they can’t convert into victory. They were optimizing for the wrong thing.

The Timing Trap

Perhaps the cruelest aspect of the promotion paradox is that excellence can arrive at the wrong moment. In chess, you can dominate for thirty moves, build a winning position, and then watch helplessly as your opponent finds the one defensive resource you missed. All that prior excellence? Irrelevant.

The position rewards timing, not accumulated credit. There’s no bank where you can store your good moves and withdraw them later when you really need them.

This is why consistently good performance isn’t enough. The person who delivers results when it doesn’t matter much, but fails when stakes are high, won’t advance as far as the person who shows up precisely when it counts. Even if their average performance is lower.

The game demands that you be excellent at the moment of evaluation, not in general. And you often don’t know when that moment will arrive.

What Actually Gets Rewarded

Strong players develop a skill that’s hard to describe but obvious when you see it. They make the position simpler when they’re winning and more complex when they’re losing. They understand not just what’s good, but what’s appropriate for this specific situation.

This is judgment. Not judgment about whether a move is objectively sound, but judgment about what this position needs right now.

Someone operating at a higher level doesn’t necessarily calculate better or know more opening theory. They might not even make fewer mistakes. But they make different kinds of mistakes. They err strategically, not tactically. And when they’re right, they’re right about things that matter.

This is what evaluators look for, often unconsciously. Not who’s most competent at current tasks, but who demonstrates the kind of judgment needed at the next level. Who sees the board the way someone at that level needs to see it?

The Path Forward

The promotion paradox can’t be solved by simply working harder at your current role. That’s like trying to promote a pawn by moving it backward to defend it better. The pawn promotes by advancing, which necessarily means leaving safety behind.

Advancement requires demonstrating capabilities beyond your current position while still performing it adequately. This is the tight rope. Neglect your current role entirely, and you create problems. Focus on it exclusively, and you signal that you’re optimized for where you are, not where you could be.

The strongest players develop a split focus. They handle their immediate responsibilities with enough of their attention to avoid disasters. But their real concentration goes toward understanding the larger game. What’s the position really about? What will matter three moves from now, or five moves from now? What’s the plan that justifies all these preparatory moves?

They’re playing the current position while simultaneously playing the position they want to create. This dual awareness is what separates levels of mastery.

The Real Competition

Here’s the final insight chess offers about advancement. You’re not really competing against other people. You’re competing against the position itself.

The board doesn’t care about your credentials or track record. It cares about whether you found the right move now, in this position, with these specific pieces and this exact pawn structure. All your past brilliance won’t help if you misunderstand what the current situation requires.

This is strangely liberating. It means advancement isn’t about being universally better than everyone else. It’s about being right about what matters when it matters. Sometimes that’s you. Sometimes it isn’t. But excellence at your current level only indicates you’ve mastered your current level. The next level is a different game entirely, played on the same board.

The pieces don’t change. The board doesn’t change. But everything about how you need to see them does.