Table of Contents

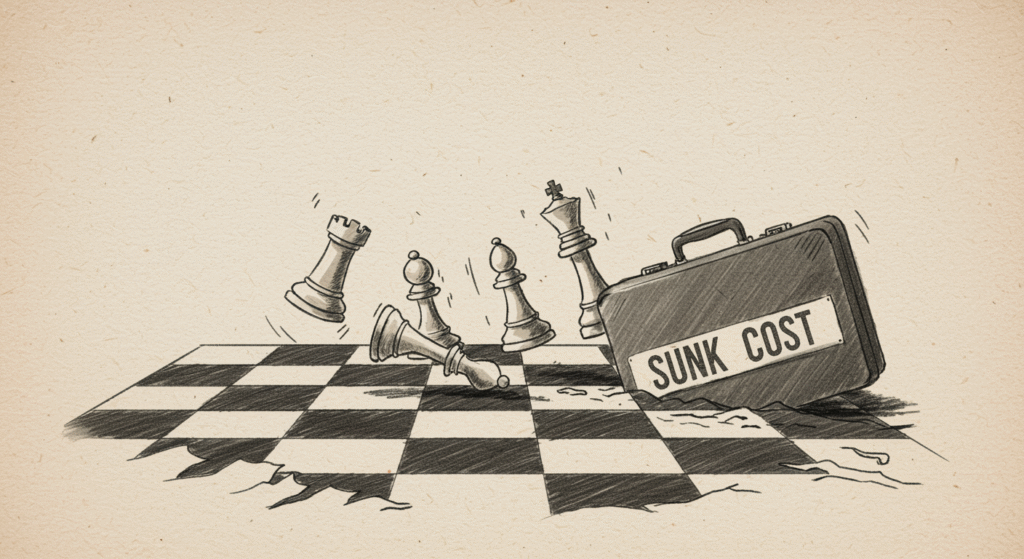

The queen hangs undefended on the board. Three moves ago, she was perfectly positioned. Two moves ago, things started looking suspicious. One move ago, alarm bells rang. But the player stares at the board, calculating elaborate escape routes, sacrificing pawns to create a corridor, twisting the position into increasingly complex knots. All to save a piece that should have retreated five moves earlier.

Anyone who has played chess for more than a few months recognizes this trap. The stubborn refusal to admit that an investment has gone wrong. The determination to make a bad plan work through sheer force of will. Chess players call it “hope chess” or “playing on tilt.” Economists call it the sunk cost fallacy. Business consultants call it throwing good money after bad. But whatever you call it, it’s the silent killer of promising positions and profitable ventures alike.

The Psychology of the Trapped Queen

Something strange happens in our brains when we commit resources to a project. Each hour spent, each dollar invested, each piece of reputation staked creates an invisible weight. That weight doesn’t make the project more valuable. It doesn’t improve the odds of success. But it makes walking away feel like admitting defeat.

Research in behavioral economics has shown this pattern repeatedly. People stay in failing relationships because of years invested. Businesses continue funding doomed products because of money already spent. Nations escalate wars because of soldiers already lost. The logic is backwards, but the emotion is universal.

Chess strips this dynamic down to its essence. Every piece sacrificed in an attack represents sunk cost. Every tempo lost to a dubious plan represents invested time. And unlike business, where quarterly reports can obscure reality for months, chess provides immediate feedback. The opponent punishes hesitation. The clock punishes indecision. The position itself reveals truth.

When the Attack Fails

Picture a chess player who launches a kingside attack. Pieces flow toward the enemy king. Pawns march forward. The plan looked brilliant three moves ago. But the opponent defended accurately. What looked like a breakthrough became a dead end.

Now the attacker faces a choice. Continue pushing, hoping the opponent makes a mistake. Or acknowledge that the attack has stalled and regroup. The pieces committed to the attack are out of position. They cannot easily retreat. But pushing forward means weakening the position further, creating holes the opponent will exploit.

Strong players make this decision quickly. They assess whether the attack can succeed with perfect play. If not, they cut their losses. They retreat pieces even if it feels humiliating. They transition to a defensive setup even if it means admitting the attack failed. Weak players cling to their original plan, pouring more resources into a failed strategy until the position collapses.

The parallel to business is exact. A company launches a new product line. Initial results disappoint. But the team has spent months developing it. The CEO has promised shareholders. Marketing has committed budget. So instead of pivoting, they double down. More advertising. More features. More excuses. Meanwhile, competitors who cut their losses early move on to better opportunities.

The Poisoned Pawn

One of the most instructive positions in chess involves the poisoned pawn. An opponent offers material, usually a pawn, in a tempting location. Taking it looks profitable. Free material with no obvious downside. But the time spent capturing the pawn and the awkward position of the capturing piece create hidden costs.

Beginners grab the pawn immediately. Intermediate players have learned to calculate whether the pawn is truly poisoned. Advanced players understand something deeper. Even if the pawn is objectively safe to capture, taking it might commit them to a path that limits options later. Sometimes the best move is to ignore free material entirely because accepting it would distort the position in unhelpful ways.

This concept translates directly to opportunity cost in business and life. A job offer arrives with a slightly higher salary but requires relocating to a city you dislike. A client requests additional features that would delay your product launch by months. A friend asks for help with a project that would consume your weekends for the foreseeable future.

None of these opportunities are necessarily bad. But accepting them means rejecting alternatives. The salary bump means giving up the career network in your current city. The client features mean missing the market window. Helping the friend means abandoning your own projects. Chess players who grab every hanging piece often find themselves with material advantage but terrible positions. Similarly, people who say yes to every opportunity often find themselves busy but unfulfilled.

The Endgame Principle

Chess endgames teach a brutal lesson about sunk costs. With few pieces remaining, every move matters exponentially. Players often reach positions where they have invested tremendous energy building an advantage, only to realize in the endgame that their advantage cannot convert to victory.

A player might be up a pawn, the equivalent of having more resources than the opponent. But if that pawn cannot advance to promotion, it’s worthless. The advantage is theoretical, not practical. Strong players recognize these dead drawn positions immediately. They offer draws even when technically ahead, because they understand that “ahead” means nothing if the position cannot be won.

Weak players keep pushing. They maneuver for fifty moves. They refuse the draw. They invest hours trying to squeeze water from stone. Eventually they either agree to the draw anyway or lose on time, having wasted energy that could have gone to the next game.

The business equivalent appears constantly. A startup pivots three times trying to make their original vision work, burning through runway that could have funded a completely different venture. A writer spends years revising a manuscript that six publishers have already rejected, instead of starting a new project. An engineer debugs legacy code for months when rewriting from scratch would take weeks.

The question is never whether you have invested resources. The question is whether continued investment will generate returns. Chess makes this calculation visible on the board. Life requires more courage to face the same math.

The Strength of Flexibility

The best chess players share a common trait. They make plans, but hold them loosely. They commit to strategies, but remain ready to abandon them. They invest pieces in positions, but retreat without ego when circumstances change.

In practical terms, it means staying emotionally detached from your previous decisions. The position you have now is the only position that matters. What you planned five moves ago is history. What you hoped would happen is irrelevant. The only question is what gives you the best chance from this position forward.

This mindset applies perfectly to project management. Imagine a software team six months into a twelve month project. They discover a new technology that could accomplish their goals in three months. But adopting it means discarding six months of work. The sunk cost fallacy says keep going. Rational analysis says switch technologies. The six months are gone regardless. The only question is whether the next six months are better spent finishing the old approach or adopting the new one.

The Meta Lesson

Chess teaches the sunk cost lesson so effectively because it removes ambiguity. You cannot lie to yourself about whether a position is winning. You cannot hide behind political explanations for why your strategy failed. The opponent does not care about your intentions or your efforts. They care about whether you can deliver checkmate.

Business and life offer more room for self deception. You can blame market conditions. You can point to external factors. You can find small victories within large defeats. This flexibility is sometimes healthy, providing resilience against temporary setbacks. But it also enables the sunk cost fallacy to flourish.

The chess board is merciless in a useful way. It forces honesty. And honest assessment is the antidote to sunk cost thinking. Not optimism or pessimism, but clear eyed evaluation of whether continuing on the current path makes sense given what you know now.

Practical Application

So how do you actually implement this lesson? How do you distinguish between valuable persistence and foolish commitment to a failing plan?

Chess suggests three diagnostic questions. First, if you were starting from the current position with no history, would you choose this plan? If not, why are you continuing it? Second, what would need to be true for this plan to succeed, and are those conditions realistic? Third, what alternatives exist, and why are they worse than pushing forward?

These questions strip away the emotional weight of past decisions. They force you to evaluate the situation as it is, not as you wish it were. They make visible the often invisible costs of continuing a doomed project.

The hardest part is not asking these questions. It’s acting on the answers. A chess player who correctly identifies that their attack has failed but continues attacking anyway has learned nothing. Similarly, a business leader who knows a project is doomed but continues funding it has failed the test.

Conclusion

Every chess player remembers the game where they refused to give up the lost position. They played on for thirty pointless moves. They tried combinations that couldn’t work. They hoped their opponent would blunder. And eventually, they lost anyway, having wasted time and energy that could have gone to the next game.

The lesson is simple but not easy. Past investments do not justify future ones. Every move should be evaluated on its own merits from the current position. Emotional attachment to previous plans is the enemy of good decision making. And the ability to let go, to retreat, to abandon failing strategies is not weakness but wisdom.

The board teaches this lesson over and over. The question is whether we are willing to learn it.