Table of Contents

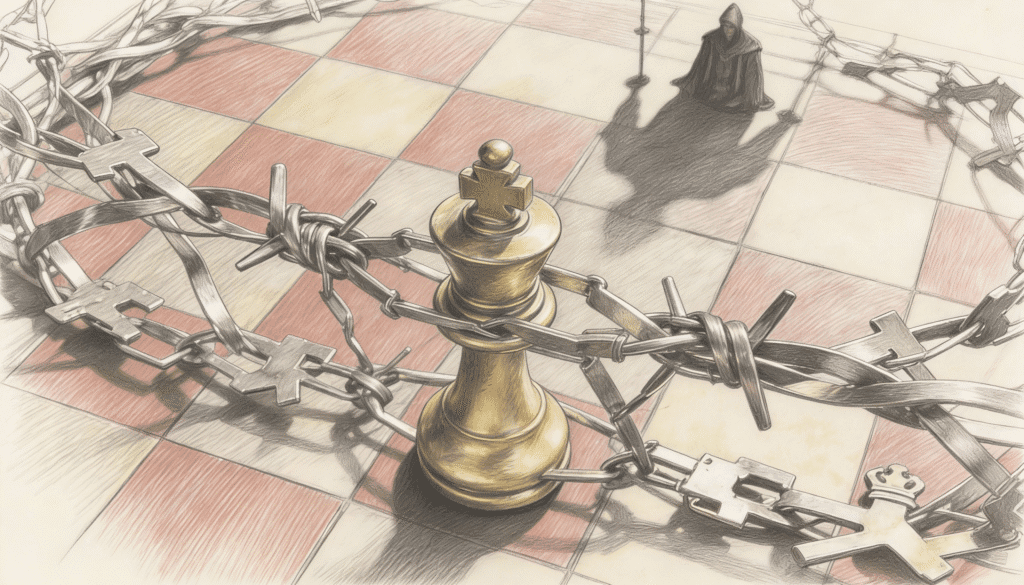

The board is tilted against you. Your king stands exposed, pieces scattered like soldiers after a surprise attack. Your opponent leans forward, sensing victory. The clock ticks. Your hand hovers over the pieces, trembling slightly. This moment arrives for every chess player, and what happens next reveals something profound about human nature under stress.

Most people think chess is about attacking. The movies show genius players launching brilliant assaults, sacrificing pieces in spectacular combinations that leave opponents stunned. But anyone who has spent serious time with the game knows a different truth. The real test of a chess player isn’t how they attack when everything is going well. It’s how they defend when everything is falling apart.

Defense under pressure is where chess becomes a mirror for life itself. The skills learned while struggling to hold a collapsing position transfer to job interviews, difficult conversations, financial setbacks, and moments when life corners you with no obvious escape. The chessboard becomes a training ground for the mind’s ability to function when panic wants to take over.

When the Storm Arrives

Consider what happens in the mind during a crisis on the chessboard. A player has been building their position carefully for twenty moves. Then comes a single oversight. The opponent finds a breakthrough. Suddenly, threats multiply like shadows at sunset. The natural response is the same one humans have carried since ancient times. The heart rate increases. Thoughts become scattered. The urge to do something, anything, becomes overwhelming.

This is where most defensive efforts fail. Not because the position is lost, but because the defender makes it lost through panic. They lash out with desperate moves that ignore the real threats. They try to create counter attacks when their house is on fire. They abandon the very pieces that could save them while chasing irrelevant gains on the other side of the board.

Chess teaches a brutal but valuable lesson. Panic is not just unhelpful under pressure. It is the actual enemy. The external threat, no matter how severe, becomes winnable once the internal chaos is controlled. The player who can quiet their mind while their position crumbles has already won half the battle.

The Art of Clear Thinking in Chaos

Defending under pressure demands a specific type of thinking that runs counter to instinct. When threatened, humans want to expand their options, to flail in every direction searching for escape. Chess teaches the opposite approach. It teaches narrowing. It teaches focus so sharp that the board shrinks to only what matters right now.

This shift in thinking changes everything. The defender stops trying to control the uncontrollable and focuses entirely on the opponent’s immediate threats. Can the attack be blocked? Can the attacking piece be captured? Can the valuable piece under attack be moved to safety? These questions are concrete, answerable, and actionable. They transform an overwhelming situation into a specific problem.

The Calculation of Survival

Defending under pressure requires something that sounds simple but proves remarkably difficult. It requires honesty. The defender must see the position exactly as it is, not as they wish it to be. This is harder than it sounds.

A player who has been winning often sees their position through a distorted lens when things turn bad. They still believe they’re better because they were better ten moves ago. This blindness kills more positions than any tactical oversight. The defender who can accept reality instantly, who can say “I am worse now and must fight to survive,” gains an enormous advantage over someone still living in the past.

Chess teaches players to assess positions with cold clarity even when emotions run hot. What material remains? Which pieces are active and which are passive? What weaknesses exist that the opponent can target? What defensive resources remain unused? These questions must be answered truthfully, without sugar coating or despair. Both optimism and pessimism are enemies of accurate assessment.

This trained objectivity becomes a life skill. People who play chess seriously often develop an unusual ability to evaluate bad situations without catastrophizing. They’ve learned that even terrible positions sometimes hold unexpected defensive resources. But they’ve also learned that wishful thinking doesn’t move pieces.

Finding Resources in Empty Pockets

The most fascinating aspect of defensive chess is discovering that hopeless positions often aren’t hopeless at all. The board that looks completely lost to a panicked mind often contains hidden defensive possibilities. Finding them requires a shift in perspective.

Defenders learn to look for what chess players call counterplay. When direct defense becomes impossible, the defender seeks their own threats. Not random attacks, but specific threats that force the opponent to pause their assault and deal with something urgent. This creates time. Time to reorganize. Time to bring reinforcements. Time to find better defensive setups.

This strategic principle appears constantly outside chess. People facing overwhelming professional challenges learn that sometimes the best defense is creating something that demands attention. Someone being dominated in a negotiation shifts the conversation to a topic where they hold more knowledge. Someone facing aggressive questioning deflects with a carefully placed question of their own. These aren’t evasions. They’re tactical pauses that change the rhythm of the exchange.

Chess also teaches defenders to maximize what little they have. A single piece, positioned perfectly, can sometimes hold off multiple attacking pieces. The concept seems mathematically impossible, but it happens regularly on the chessboard. It happens because space matters as much as material. A well placed defender controls key squares that the attacker must pass through, creating a bottleneck.

This translates directly to resource management under pressure in other domains. The person with limited time learns to position that time at the exact moment it creates maximum impact. The small business facing larger competitors learns to occupy the specific market niche that big companies can’t efficiently contest. The student with limited study time learns to focus on the areas most likely to appear on the exam.

The Endurance Test

What chess reveals about defense that few other activities do is how it tests endurance. Defending under pressure is exhausting. It offers no glory, no brilliant moves that spectators applaud. It’s grinding, move after move, holding the line, finding the least bad option repeatedly.

This is why so many players collapse in defensive positions even when the position remains defensible. They simply run out of mental stamina. The burden of constant accuracy, the stress of knowing that each move could be the fatal error, drains energy at an astonishing rate. Chess teaches that pressure is a weapon in itself, separate from the specific threats on the board.

The players who become excellent defenders develop unusual mental endurance. They train their minds to maintain focus through discomfort. They accept that defending means playing under stress for extended periods without relief. This isn’t fun, but it’s real. Life rarely asks people to perform at their best when rested and comfortable. It asks them to perform when tired, stressed, and overwhelmed.

The Moment of Escape

Eventually, something shifts. The defender who has held the line long enough often finds that their opponent’s attack has exhausted itself. The threats that seemed infinite were actually finite. The attacker pushed too hard and overextended. Pieces that were menacing now stand awkwardly placed, unable to retreat efficiently.

This is the moment chess teaches patience for. The defender who survives the storm often emerges in an equal position, sometimes even better. The attacker used energy and resources creating threats. When those threats don’t lead to immediate victory, they become liabilities. The game transforms. Sometimes the defender becomes the attacker, pursuing the very opponent who seemed unstoppable minutes earlier.

This pattern appears everywhere. Markets crash and those who defended their positions without panic selling find themselves holding valuable assets when others have been shaken out. Relationships weather terrible fights and couples who stayed engaged through the difficulty often find themselves closer afterward. Projects that seemed doomed hit turning points where persistence pays off spectacularly.

The Practice Ground

Chess provides something rare and valuable. It provides a safe space to practice falling apart and recovering. Each game offers multiple moments of pressure, multiple chances to feel that stomach dropping sensation of seeing a threat you didn’t anticipate. Over hundreds or thousands of games, players develop emotional resistance to pressure itself.

This is different from confidence. Confidence can be false, built on success that hasn’t faced real testing. What chess builds is something more reliable. It builds familiarity with pressure. The experienced player has been in desperate positions so many times that desperation itself becomes a known state rather than an unfamiliar one. The mind processes it differently when it’s familiar terrain.

Young players often quit when they start losing. They can’t tolerate the feeling of playing from behind. The players who push through this phase and continue playing despite losses develop something valuable. They learn that losing positions are playable. They learn that opponents make mistakes. They learn that escape routes exist in situations that initially seem closed.

The Transfer to Life

The ultimate value in learning defense under pressure through chess is how naturally it transfers beyond the board. The mental habits formed during desperate games manifest automatically in other high pressure situations. The ability to quiet panic, assess honestly, focus narrowly, and persist through discomfort becomes a general life skill.

People who play chess seriously often notice they handle crisis differently than others. Not because they’re smarter or braver, but because they’ve practiced the specific mental routines that work under pressure. They’ve learned through repeated experience that their first instinct in a crisis is usually wrong. They’ve learned to pause, breathe, and think clearly when everything in them wants to react immediately.

The chessboard is a laboratory for human behavior under stress. Every game offers lessons about maintaining composure, finding resources, and outlasting difficulties. These lessons arrive not through lectures but through visceral experience. The player remembers the game where they survived an impossible attack because they learned something real about themselves and about pressure.

Defense under pressure is where chess stops being a game and becomes something more. It becomes training for the inevitable moments when life attacks and survival requires every mental resource available. The next time you see someone deep in thought over a losing chess position, understand they’re not just playing a game. They’re practicing for reality.