Table of Contents

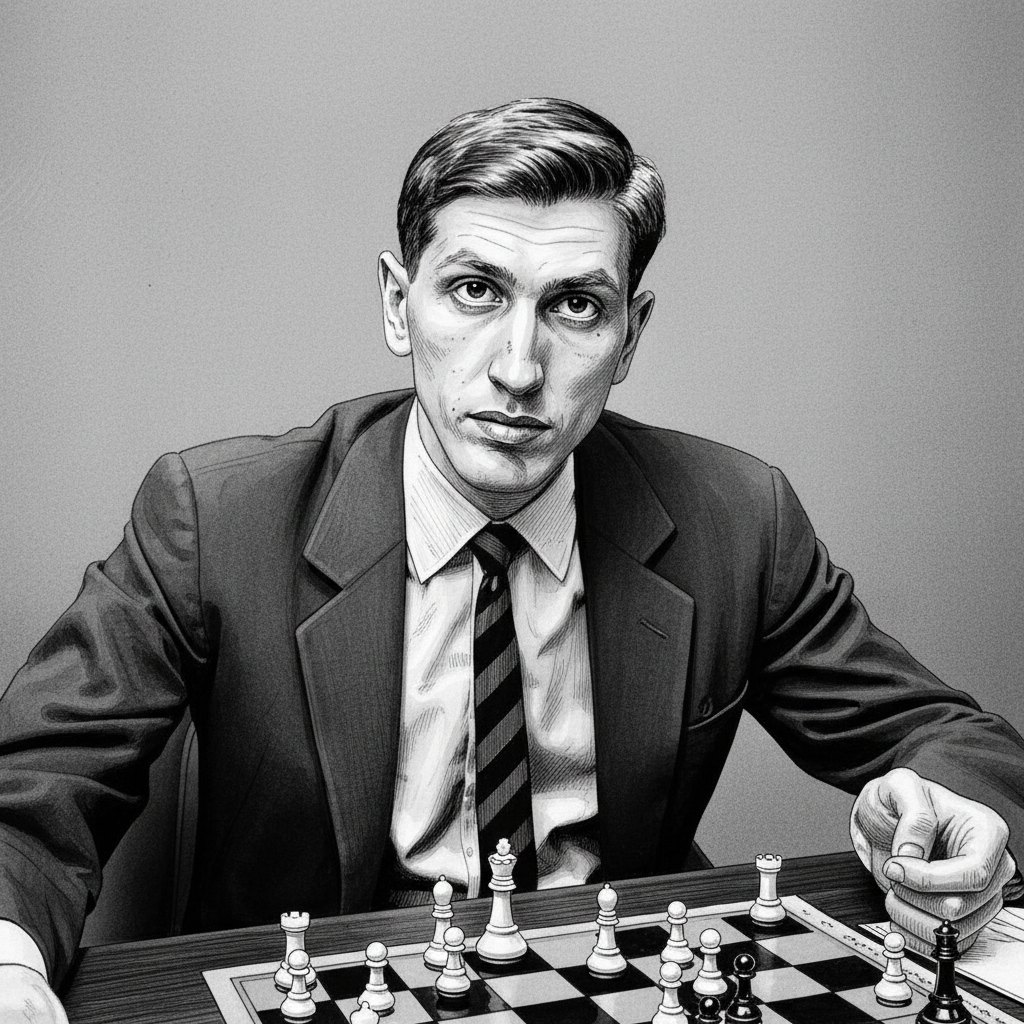

In June 2000, a nine-year-old Norwegian boy sat down to play chess with a rating of 904. By August 2019, that same player would stand atop the chess world with a rating of 2882—the highest in history. This is the story of Magnus Carlsen’s extraordinary ascent, a journey that redefined what’s possible in the ancient game of chess.

But this wasn’t a straight climb up a mountain. It was a story told in five distinct chapters, each marking a transformation not just in numbers, but in the very essence of how one human being could master the 64 squares.

Phase 1: The Explosion (2000-2002) — From 904 to ~2000

The transformation began with a spark.

In the year 2000, young Magnus Carlsen was being coached at the Norwegian College of Elite Sport by Grandmaster Simen Agdestein, Norway’s top player. But something extraordinary was about to happen—something that would make even seasoned chess observers do a double-take at the rating lists.

Over the course of a single year, Carlsen’s rating rose from 904 in June 2000 to 1907—a gain of more than 1,000 points in twelve months. To put this in perspective, most chess players would consider a 100-point gain in a year to be exceptional progress. Magnus had achieved ten times that.

But the numbers alone don’t capture the real story. This wasn’t just about a talented kid winning games. This was about someone who was beginning to see patterns that others couldn’t, who was absorbing the game at a rate that defied normal learning curves.

His breakthrough occurred in the Norwegian junior teams championship in September 2000, where he scored 3½/5 against the country’s top junior players and gained a tournament performance rating of around 2000. In that moment, playing against Norway’s best young talents and holding his own, Magnus crossed an invisible threshold. He was no longer just a promising youngster. He was a force.

From autumn 2000 to the end of 2002, Carlsen played almost 300 rated tournament games, devouring experience like a chess computer processing millions of positions. While other kids his age were playing video games and chasing footballs, Magnus was locked in combat across the board, accumulating knowledge, patterns, and the battle-hardened instincts that only come from constant play.

This phase was about raw accumulation—rating points, yes, but more importantly, the foundational understanding that would support everything to come. The explosion had occurred. Now came the refinement.

Phase 2: The Prodigy Emerges (2003-2007) — Breaking 2700

By early 2004, the chess world was starting to notice the teenager from Norway. In January of that year, competing in the C group of the prestigious Corus tournament in Wijk aan Zee, Netherlands, thirteen-year-old Carlsen dominated the tournament, best exemplified in a game won with a 29-move checkmate. American chess writer Lubomir Kavalek famously dubbed him “the Mozart of chess.”

But Mozart or not, Magnus still had to earn his credentials.

In April 2004, at 13 years, four months and 27 days of age, Carlsen became the second-youngest grandmaster at the time, trailing only Sergey Karjakin’s record. The title was significant, but it was what happened just before that crystallized Magnus’s arrival on the world stage.

In March 2004, at a blitz tournament in Reykjavik, Iceland, something remarkable occurred. The teenage Carlsen defeated former world champion Anatoly Karpov and drew a game against another former champion, Garry Kasparov.

Imagine being thirteen years old and sitting across from Kasparov—arguably the greatest player in history at that point—and holding your own. That takes more than chess skill. That takes steel nerves and an unshakeable belief in your own abilities.

The years that followed saw Magnus navigating the treacherous waters between prodigy and elite player. This is where many promising youngsters falter—they dominate age-group tournaments but struggle when the competition gets serious. Not Magnus.

In 2007, Carlsen won the Biel Grandmaster Tournament with 6/10 points and a performance rating of 2753, overcoming a field that included four players in the world’s top 25. This wasn’t a junior tournament or an age-restricted event. This was beating elite grandmasters in their prime, and Magnus was still a teenager.

By the end of this phase, Carlsen had broken through 2700, entering the super-elite tier of chess. But more than the rating, he had developed something more valuable: the psychological fortitude to compete with anyone, anywhere, at any time.

Phase 3: The Sprint to 2800 (2008-2009) — Becoming Unstoppable

If the previous phase was about establishing credibility, this phase was about announcing dominance.

The year 2008 marked the beginning of Magnus’s assault on the top of the chess world. In the elite Wijk aan Zee tournament, facing a field where eleven of the fourteen players were ranked in the world’s top sixteen, Carlsen achieved a performance rating of over 2800. Then, in June, he won the Aerosvit chess tournament, finishing undefeated with 8/11 and achieving a performance rating of 2877, his best at that point in his career.

Performance ratings are theoretical numbers that represent how well you played in a specific tournament. To consistently produce performance ratings in the 2800s meant Magnus wasn’t just competing at the top level—he was often the best player on the board.

But the performance that truly shocked the chess world came in September 2009.

At the Pearl Spring Chess Tournament, Carlsen won with 8/10 points, finishing 2.5 points ahead of the top-rated player in the world at the time, Veselin Topalov, with a tournament performance rating of 3001. Read that number again: 3001. To understand how absurd this is, consider that no one has ever had an official rating above 2900. Magnus had produced a performance that theoretically exceeded the highest rating ever achieved by over 100 points.

In 2009, at age eighteen, Carlsen became the youngest player to break the 2800-rating threshold (a record later broken by Alireza Firouzja in 2021). Crossing 2800 isn’t just a milestone—it’s a statement. At that time, only a handful of players in history had ever reached that height. Magnus had done it before his nineteenth birthday.

The teenager from Norway wasn’t just talented. He was transcendent. And he was just getting started.

Phase 4: The Peak (2010-2014) — Touching 2882

The early 2010s saw Magnus consolidate his position at the absolute summit of chess. In January 2010, FIDE announced that Carlsen was the top player in the world. He had recently turned 19 and was thus the youngest player to be ranked number one.

But being ranked number one wasn’t enough. Magnus had his eyes on something bigger: becoming world champion and pushing the rating system to its absolute limits.

In November 2013, Carlsen defeated Viswanathan Anand in Chennai, India, with a score of 3 wins and 7 draws, becoming the second youngest world champion after Kasparov. The title had eluded him for years, but now it was his. And with the champion’s crown came a surge of confidence and performance.

What happened next was historic.

In the May 2014 rankings, Carlsen achieved an all-time high record of 2882. On April 21, 2014, during the Shamkir Chess tournament, his live rating hit 2889.2, both the highest ratings ever achieved in classical chess.

Think about what this means. The rating system had existed for decades. Legends like Bobby Fischer, Garry Kasparov, Anatoly Karpov, and countless others had competed under it. And Magnus Carlsen, at twenty-three years old, had climbed higher than any of them.

But perhaps what’s most remarkable about this achievement is how Magnus approached the game. Carlsen uses a variety of openings to make it harder for opponents to prepare against him and reduce the utility of pre-game computer analysis. While others tried to find the “best” moves through computer preparation, Magnus believed in something more fundamental: Carlsen has stated that the middlegame is his favourite part of the game as it comes down to “pure chess”.

This was chess stripped of all its artifice—no gimmicks, no tricks, just superior understanding and relentless pressure. It was beautiful, it was brutal, and it was effective beyond measure.

Phase 5: The Return to Everest (2019) — Equaling the Peak

For five years after May 2014, Magnus remained the world’s number one player, defending his world championship title multiple times. But his rating hovered in the 2850s, never quite returning to that magical 2882 mark. Some wondered if that peak had been a moment of lightning in a bottle—brilliant, but unrepeatable.

Magnus had other ideas.

The first half of 2019 saw Carlsen playing some of the most dominant chess of his career. He went on an extraordinary run, winning tournament after tournament with seemingly effortless superiority. It was during this period that he set another record: 125 classical games in a row without defeat between July 2018 and October 2020.

Tournament victories piled up: Norway Chess, Lindores Abbey Chess Stars, Côte d’Ivoire Rapid & Blitz. Each win pushed his rating higher, closer to that summit he’d reached five years earlier.

Then came the Grand Chess Tour tournament in Zagreb, Croatia. From 26 June to 7 July, Carlsen participated in the second leg of the 2019 Grand Chess Tour, held in Zagreb. He took clear first with 8/11 (+5−0=6), and improved his rating to 2882, equalling his peak set in 2014. This was Carlsen’s eighth consecutive tournament victory.

In terms of level of opponents, Carlsen played 79 games against opponents whose rating averaged 2764, for a 2888 performance rating in the past year—demonstrating that this wasn’t about beating weak opposition. This was about systematically dismantling the world’s best players.

Colleagues outdid each other with superlatives to describe the Norwegian’s stratospheric rise: Wesley So compared Carlsen’s dominance to Fischer in the 1970s, when everyone else was “just playing for second place.” Anish Giri joked that we would just have to wait until “the storm passes,” because at some point Carlsen would become “very old and tired.” Until then, he would be untouchable.

Magnus Carlsen had returned to Everest. And this time, he’d proven it wasn’t a fluke. He could reach the highest peak in chess history, leave, and come back five years later to touch it again. It was a feat of consistency and excellence that may never be matched.

The Legacy: What the Numbers Really Mean

From 904 to 2882. From a nine-year-old Norwegian child to the highest-rated chess player in history. The numbers tell a story, but they don’t tell the whole story.

Magnus Carlsen’s rating ascent isn’t just about natural talent, though he clearly has that in abundance. It’s about an almost inhuman work ethic in his youth—playing nearly 300 games in two years. It’s about the courage to face legends like Kasparov and Karpov as a teenager and not flinch. It’s about the strategic brilliance to realize that in an age of computer preparation, the real battles are won in the middlegame, where pure chess understanding reigns supreme.

Carlsen has held the No. 1 position in the FIDE rankings since 1 July 2011, the longest consecutive streak, a span of over a decade of uninterrupted dominance. No one in the modern era has controlled chess so completely for so long.

Perhaps most tellingly, when Magnus announced in 2022 that he wouldn’t defend his world championship title, citing a lack of motivation, he had already cemented his legacy. He didn’t need the title to prove he was the best. The rating—that number that followed him from 904 to 2882—had already told that story.

Today, when young chess players around the world study the game, they’re not just learning openings and tactics. They’re learning to think like Magnus—to play with flexibility, to embrace complexity, to grind down opponents through superior understanding rather than memorized lines.

The five phases of Magnus Carlsen’s rating ascent represent more than a mathematical progression. They represent a revolution in chess, a new standard of excellence, and a reminder that even in a game as old as chess, there are still mountains left to climb—and for one Norwegian genius, the summit of 2882 will forever stand as testament to how high one person can soar.