Table of Contents

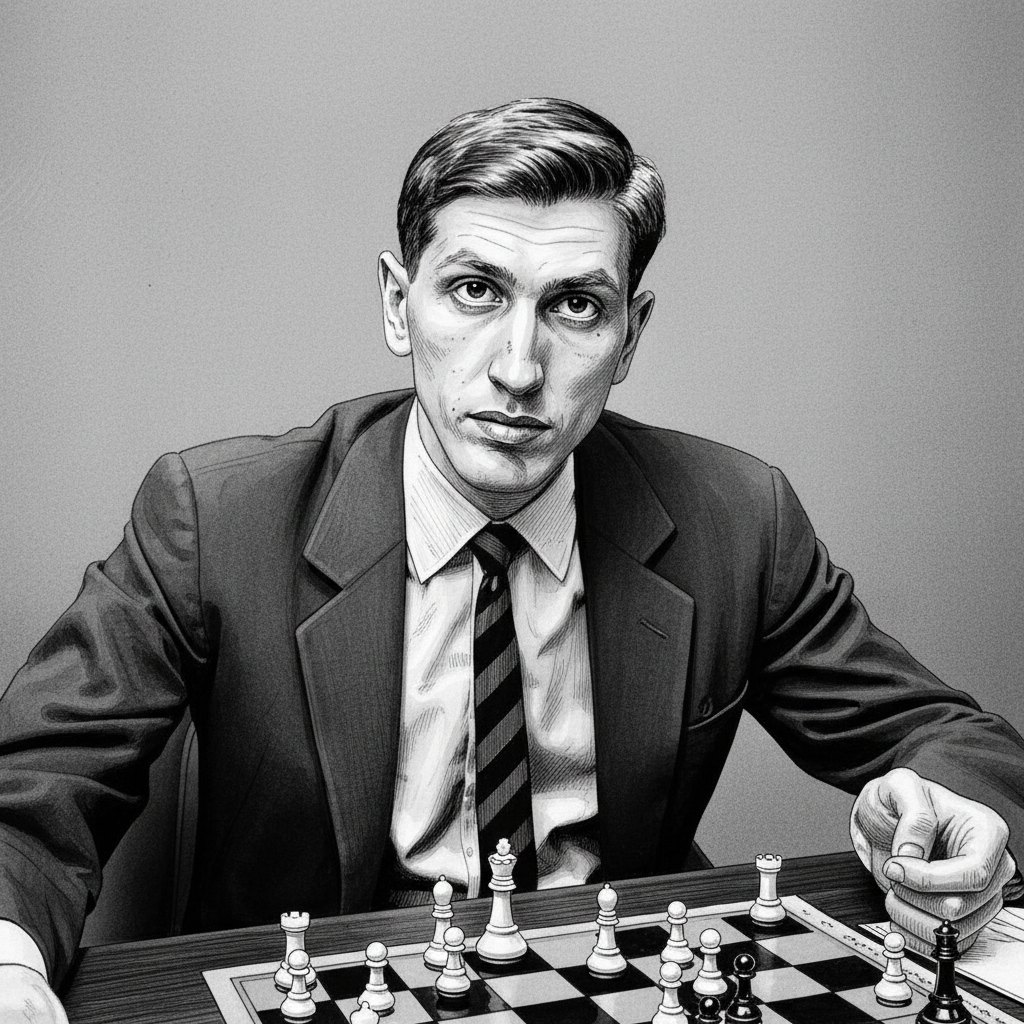

The year was 1984, and the World Chess Championship had been grinding on for five months. Forty-eight games. No winner. Anatoly Karpov, the reigning champion, looked gaunt and exhausted, having lost 22 pounds. His challenger, a 21-year-old Garry Kasparov, sat across from him with fire still burning in his eyes. The match was eventually called off without a winner—an unprecedented move in chess history. But something else unprecedented was happening: chess had become warfare.

For decades, chess had been portrayed as the gentleman’s game, a cerebral pursuit conducted in hushed reverence, where masters moved pieces with delicate fingers and nodded politely at their opponent’s brilliance. Then came Kasparov, and suddenly chess looked less like a drawing room pastime and more like a prizefight. He didn’t just play chess. He attacked it, dominated it, and transformed it into something visceral and electrifying. Garry Kasparov made chess a contact sport, and the game would never be the same.

The Boy from Baku Who Learned to Fight

Garry Kimovich Kasparov was born in 1963 in Baku, Azerbaijan, as Garik Weinstein. His father, a Jewish electrical engineer, died when Garry was seven. His mother, Klara Kasparova, an Armenian engineer, became the driving force behind his chess career, and young Garry eventually took her surname. From the beginning, chess wasn’t just a game for him—it was identity, purpose, and destiny rolled into one.

But what set Kasparov apart wasn’t just his prodigious talent. Plenty of children showed brilliance at the chessboard. What made Kasparov different was his temperament. While other young players were taught to maintain poker faces and emotional neutrality, Kasparov played with his whole body. He fidgeted. He glared. He radiated intensity from every pore. When he spotted a winning combination, his eyes would flash with predatory excitement. When his opponent found a good defense, you could see the frustration ripple across his face.

This wasn’t poor sportsmanship—it was authenticity. Kasparov refused to pretend that chess was some abstract intellectual exercise divorced from human emotion. For him, every game was personal. Every move carried weight. Every victory or defeat meant something beyond the 64 squares in front of him.

The Karpov Wars: When Chess Became Gladiatorial

If Kasparov was the man who made chess a contact sport, then Anatoly Karpov was the establishment he crashed into like a wrecking ball. Their rivalry defined an era and remains the most intense in chess history.

Karpov was everything the Soviet chess establishment loved: controlled, systematic, methodical. He squeezed opponents slowly, like a python, until they suffocated under the pressure of his technique. He was the perfect Soviet champion—no scandals, no drama, just pure chess excellence wrapped in an unassuming package.

Then came Kasparov, all fire and fury, representing a new generation that refused to follow the script.

Their first World Championship match in 1984 became legendary not for its chess (though the chess was magnificent) but for its brutality. The match was scheduled to be first to six wins, draws not counting. It should have lasted a few months. Instead, it became a war of attrition that stretched across five months and 48 games. Karpov jumped ahead early, leading 5-0, and seemed on the verge of victory. He needed just one more win.

But Kasparov refused to break. Game after game, he held on, drawing repeatedly, frustrating Karpov’s attempts to land the killing blow. Then something remarkable happened—Kasparov started to win. He took games 47 and 48, suddenly showing the form everyone knew he possessed. The momentum had shifted, and it showed in everything: body language, press conferences, even the way they walked to the board.

Karpov, once serene and confident, now looked haunted. Kasparov, who had been fighting for survival, now sensed blood in the water. The psychological warfare had become so intense, the physical toll so obvious, that FIDE President Florencio Campomanes made the shocking decision to stop the match without a winner, ostensibly to protect Karpov’s health.

Kasparov was furious. He believed he was about to win and that the establishment had intervened to save their champion. Whether or not that was true, the controversy only amplified the drama. This wasn’t just chess anymore—it was political intrigue, psychological warfare, and human drama all at once.

The Rematch: When Chess Stopped the World

The rematch in 1985 carried the weight of unfinished business. This time, the format was changed to a 24-game match, and the young lion was ready. Kasparov played with a ferocity that was stunning to witness. In game 16, he uncorked a king-side attack so violent, so relentlessly aggressive, that grandmasters watching couldn’t quite believe what they were seeing. This wasn’t the careful, strategic chess of the Soviet school. This was something primal.

When Kasparov won that match at age 22, becoming the youngest world champion in history, he didn’t just win a title. He won a cultural revolution. Chess in the Kasparov era would be different—more aggressive, more theatrical, more honest about the emotions churning beneath the surface.

Over the next decade, Kasparov and Karpov would play four more world championship matches, creating a rivalry that totaled 144 games—more than any other championship rivalry in history. Each match was a battle not just of chess skill but of wills. Kasparov would pace behind the board during his opponent’s thinking time, radiating nervous energy. He would slam pieces down with authority after finding a strong move. He would glare across the board, engaging in psychological warfare that was obvious to everyone watching.

Critics called him unsportsmanlike. Supporters called him human. Either way, everyone was watching.

The Physical Presence: Chess as Performance

What made Kasparov’s approach so revolutionary was his understanding that chess, despite being a mental game, had a physical dimension that had been ignored for too long. He trained his body as rigorously as his mind, swimming and working out to build the stamina needed for five-hour games. He understood that physical fitness translated directly to mental endurance in the final hours of a crucial game.

But beyond conditioning, Kasparov used his physical presence as a weapon. He would lean forward aggressively when pressing for an advantage, his body language screaming confidence and dominance. When defending, he would sit back, arms crossed, radiating defiance—I’m still here, still dangerous, still capable of turning this around.

In an era before chess became popular on streaming platforms, when most people only saw still photographs in newspapers, Kasparov ensured that every photo told a story. His face was a canvas of emotion—concentration, fury, joy, despair, triumph. Looking at photos of Kasparov playing chess is like looking at photos of a boxer in the ring. You can feel the intensity through the image.

This physicality extended to his playing style. Kasparov favored aggressive, attacking chess that created complexity and chaos on the board. While Karpov slowly improved his position with perfect technique, Kasparov would hurl pieces forward in a storm of tactical complications, creating positions so sharp that one wrong move meant instant death. His games didn’t feel like chess problems to be solved—they felt like bar fights, where both players emerged bloody but one emerged victorious.

The Deep Blue Drama: Man Versus Machine

If Kasparov’s matches with Karpov showed chess as human combat, his matches against IBM’s Deep Blue computer showed something else entirely—existential drama. When Kasparov faced Deep Blue in 1996 and 1997, the stakes transcended chess. This was about humanity itself, about whether the human mind could be replicated and surpassed by silicon and code.

In 1996, Kasparov won the match, though he lost the first game—the first time a reigning world champion had lost to a computer under tournament conditions. Kasparov’s reaction was telling. He was visibly shaken, angry not just at losing but at the implications. This wasn’t another human opponent he could psychologically intimidate or wear down physically. This was something alien.

The 1997 rematch became one of the most dramatic moments in both chess and technological history. Kasparov lost, marking the first time a computer defeated a reigning world champion in a match. But the drama extended beyond the result. Kasparov accused IBM of cheating, claiming that some of Deep Blue’s moves showed human intervention and that IBM had refused to provide game logs to prove the computer had played fairly.

Whether his accusations had merit became secondary to the spectacle. Here was Kasparov, the most dominant chess player of his generation, emotionally unraveling on the world stage, consumed by the possibility that humanity’s intellectual crown jewel had been conquered by a machine. Game 2 of the match, which Kasparov lost after what many considered an uncharacteristic blunder, seemed to break something in him. In the post-game press conference, he looked shell-shocked, defeated not just in chess but in spirit.

For Kasparov, this wasn’t an abstract competition. It was deeply personal. And that’s what made it so compelling to watch. While IBM’s engineers celebrated a technological milestone, Kasparov treated it like a death in the family. He brought humanity to a match against a machine, and in doing so, made millions of people care about something that could have been just another tech demonstration.

The Press Conference Warrior

Kasparov’s transformation of chess into a contact sport extended beyond the board itself. His press conferences were legendary, often as compelling as the games themselves. While other chess champions gave measured, diplomatic responses to questions, Kasparov held forth like a professor, politician, and provocateur all rolled into one.

He would analyze his games with brutal honesty, pointing out not just his opponent’s mistakes but his own. He would engage in psychological warfare, making bold predictions and dismissive comments about rivals. He would connect chess to politics, culture, and philosophy, refusing to let the game be reduced to mere entertainment.

When he felt wronged—by FIDE, by tournament organizers, by computer programmers—he said so, loudly and clearly. This got him in trouble more than once, but it also made him the most quotable chess player in history. Kasparov understood that in the modern media era, the narrative mattered as much as the result. Every press conference was an opportunity to shape that narrative, to add another chapter to the story of Kasparov the fighter, the champion, the man against the world.

The Legacy: Chess in the Kasparov Image

When Kasparov retired from professional chess in 2005, he left behind a game transformed in his image. The generation of players who followed—Magnus Carlsen, Hikaru Nakamura, Fabiano Caruana—all grew up in a chess world where showing emotion was acceptable, where aggression was celebrated, where trash talk and confidence were part of the game.

Modern chess, especially as it’s evolved on streaming platforms like Twitch and YouTube, owes a direct debt to Kasparov’s approach. When top players stream their games with face cameras showing every reaction, every moment of frustration or excitement, they’re following the template Kasparov established. Chess doesn’t happen in a vacuum of pure logic—it happens in the messy, emotional, physical reality of human experience.

Kasparov also changed how we think about preparation and professionalism in chess. He was one of the first to build a team of seconds and analysts, treating chess preparation like a professional sport. He trained his body as well as his mind. He studied his opponents’ psychology as carefully as their opening repertoires. Modern chess players at the highest level now approach the game with the same professionalism as professional athletes, and Kasparov was the pioneer of that approach.

The Man Behind the Warrior

After retiring from chess, Kasparov became a pro-democracy political activist in Russia, opposing Vladimir Putin’s government with the same fearlessness he showed on the chessboard. This wasn’t a random second career—it was entirely consistent with who Kasparov had always been. He was a fighter, someone who couldn’t see injustice or authoritarianism without speaking up, regardless of the personal cost.

His political activism revealed something important about his chess career: the intensity was never an act. Kasparov genuinely couldn’t do anything halfheartedly. Whether playing chess, writing books, or challenging one of the world’s most powerful political leaders, he brought the same total commitment, the same willingness to make it personal, the same refusal to pretend that what happened didn’t matter.

Chess Will Never Be the Same

Before Kasparov, chess champions were expected to be monks of the mind, displaying perfect emotional control and treating the game as a purely intellectual pursuit. Kasparov obliterated that expectation. He showed that you could be brilliant and emotional, calculating and passionate, strategic and instinctive all at once.

He made chess appointment television in an era when most people had never heard of the sport. He turned matches into events, games into stories, and positions into drama. He respected his opponents by giving them everything he had, holding nothing back, refusing to pretend that losing to them wouldn’t hurt or that beating them wouldn’t bring joy.

In making chess a contact sport, Kasparov didn’t diminish the game—he elevated it. He showed that chess was about more than finding the objectively best move. It was about will, character, courage, and the willingness to fight even when exhausted, even when behind, even when the odds seemed impossible.

Garry Kasparov played chess the way it deserved to be played—like it mattered. Like every game was a battle, every opponent a worthy adversary, every moment at the board a chance to prove something about himself and about humanity. He brought his whole self to the chessboard—mind, body, and spirit—and in doing so, he changed chess forever.

The 64 squares would never feel so small, or so electric, again.