Table of Contents

The call came on a hot summer day in 1972, and it wasn’t from just anyone. Henry Kissinger, the United States Secretary of State, had more pressing matters to attend to—Vietnam, détente with China, the ongoing Cold War. Yet there he was, on the phone with a 29-year-old chess player from Brooklyn who was threatening to throw away the opportunity of a lifetime.

“Bobby, this is the worst player in the world calling the best player in the world,” Kissinger reportedly said with diplomatic charm. “America wants you to go over there and beat the Russians.”

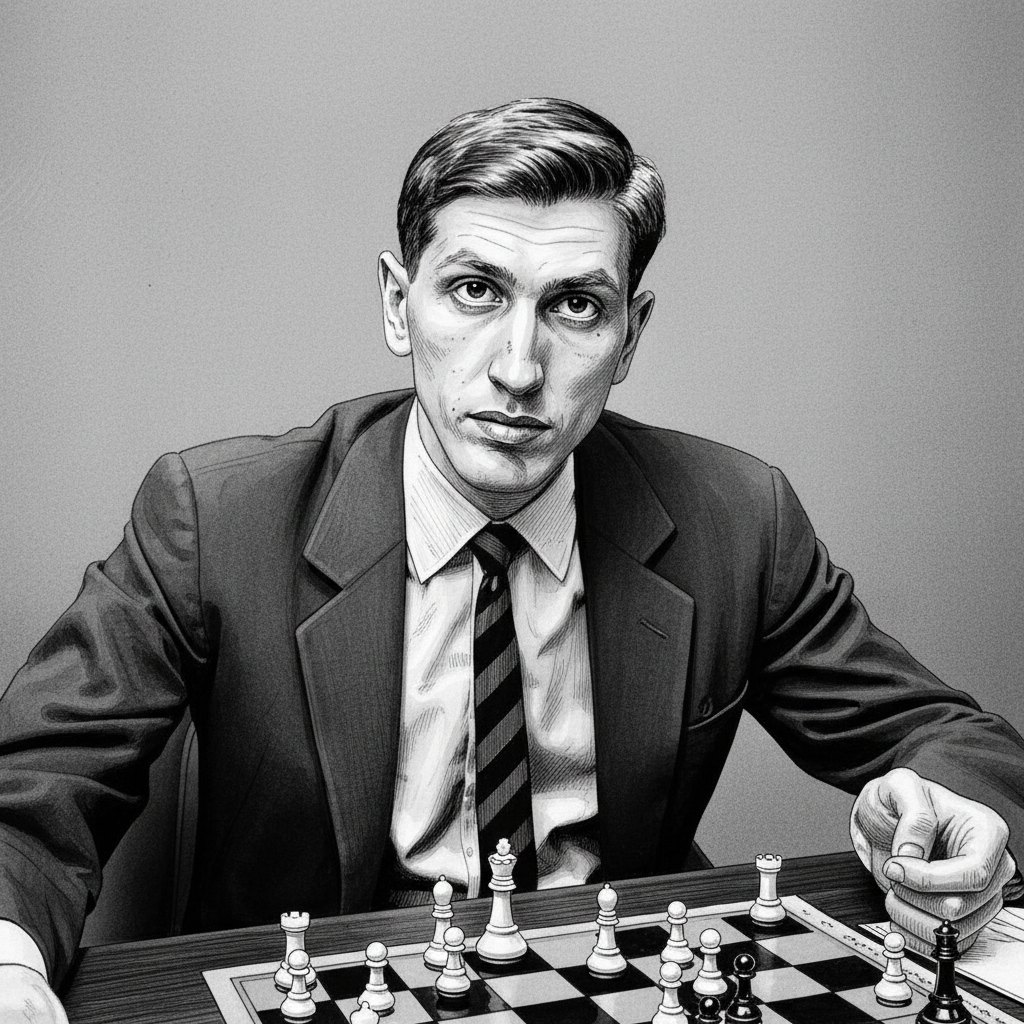

The man on the other end of the line? Bobby Fischer. The stakes? Nothing less than ending 24 years of Soviet chess domination and, in the process, transforming chess from a modestly compensated intellectual pursuit into a legitimate professional sport.

The Prodigy Who Played Himself

Robert James Fischer‘s story begins unremarkably enough—a dollar chess set purchased at a Brooklyn candy store in 1949. His six-year-old sister Joan bought it, taught him the moves, then quickly lost interest. His mother Regina, a brilliant woman who spoke six languages and held a medical degree, didn’t have time to play. So young Bobby did what would define his entire life: he played against himself.

“Fischer soon became so engrossed in the game that Regina feared he was spending too much time alone,” according to the World Chess Hall of Fame. But this wasn’t ordinary childhood obsession.

This was something different—a total, consuming dedication that his childhood friend Allen Kaufman would later describe with awe: Bobby was a chess sponge. He would walk into a room where there were chess players and he’d sweep around and he’d look for any chess books or magazines and he’d sit down and he would just swallow them one after another. And he’d memorize everything.

By age 13, Fischer became the U.S. Junior Champion. At 14, he became the youngest National Master in American history and won the U.S. Championship—the youngest player ever to do so. At 15, he became the world’s youngest International Grandmaster. These weren’t just records; they were seismic shifts in what people thought was possible in chess.

But here’s what made Fischer different from other prodigies: he didn’t just want to be good at chess. He wanted chess to be good to him—and to every professional player who came after.

The Shabby State of Professional Chess

To understand Fischer’s revolution, you need to understand what professional chess looked like in the 1960s. It was, to put it bluntly, a joke in the West. Tournament conditions were terrible—shabby, second-rate venues for lousy prizes. Players competed in dimly lit halls, sitting on uncomfortable chairs, distracted by cameras and noise, all for prize money that barely covered expenses.

In the Soviet Union, chess was different. The state supported its champions, gave them jobs with generous time off to train, and treated chess mastery as proof of communist intellectual superiority. Soviet players like Mikhail Botvinnik weren’t struggling to make ends meet—they were state-sponsored athletes in a propaganda war.

Meanwhile, Western players had to cobble together a living. Danish Grandmaster Bent Larsen wrote in 1969: FIDE expects World Championship candidates to sacrifice a lot of time and energy…but it would like them to do it as amateurs. The world championship matches themselves paid modestly. Before Fischer, even title bouts struggled to break $100,000 in prize money.

Fischer looked at this system and saw it for what it was: an insult to the game he loved. And he decided to do something about it.

The Complainer Who Changed Everything

Fischer gained a reputation as difficult, demanding, temperamental—call it what you will. He complained constantly: about lighting, about noise, about camera placement, about the color of the chess squares, about everything. Tournament organizers dreaded dealing with him. He would refuse to play, storm out of tournaments, make outrageous demands.

But here’s the thing: he was usually right.

Many top chess players today agree that Fischer’s demands for improving playing conditions and pushing for higher salaries were at least partly responsible for making chess more “professional” and bringing it into the modern era. Every “unreasonable” demand was actually Fischer fighting for something bigger—the dignity of professional chess.

He wasn’t just hypersensitive (though he may have been that too). He understood that if chess wanted to be taken seriously, it needed to look serious. It needed proper venues, proper lighting, proper compensation. It needed to be treated like a professional sport, not a hobby for academics and eccentrics.

And he had the leverage to make people listen. Because Bobby Fischer was, quite simply, unstoppable.

The Streak That Made History

In 1970, Fischer emerged from one of his periodic retirements with a singular focus: the world championship. What followed was perhaps the most dominant individual performance in chess history.

First came the Interzonal tournament, which Fischer won by 3.5 points—a commanding margin. Then came the Candidates matches, where challengers competed for the right to face the World Champion. Fischer faced Soviet Grandmaster Mark Taimanov in the quarterfinals.

He destroyed him 6-0.

Then he faced Danish GM Bent Larsen, one of the world’s elite players.

6-0 again.

This twelve-game stretch is considered by many to be the best individual performance by a chess player ever. Fischer hadn’t just won—he had crushed two world-class players without allowing them a single point. Not one draw, not one victory—nothing.

Next came Tigran Petrosian, a former World Champion and one of the craftiest defensive players in history. Fischer beat him too, though Petrosian managed to salvage some dignity by actually winning a few games.

By the time Fischer earned the right to challenge World Champion Boris Spassky, there was a record 125-point differential between the ratings of number-one ranked player Fischer and Spassky. That gap remains a record to this day. Fischer had elevated himself so far above his competition that he existed in a category of one.

The Match That Changed Chess Forever

The 1972 World Chess Championship in Reykjavík, Iceland, became known as the “Match of the Century,” and not just for the chess. It was Cold War theater at its finest—the lone American cowboy against the Soviet chess machine.

But Fischer almost didn’t show up.

The original prize fund was $125,000—already the largest in chess history. Fischer wanted more. He wanted chess to be worth more. So he refused to board his flight, even as the opening ceremony came and went. The chess world held its breath. The Soviets accused him of cowardice. The Americans pleaded with him.

That’s when British financier Jim Slater stepped in and doubled the prize fund to $250,000 (approximately $1.8 million in today’s money). As Slater once said: “Fischer is known to be graceless, rude, possibly insane. I really don’t worry about that, because I didn’t do it for that reason. I did it because he was going to challenge the Russian supremacy, and it was good for chess.”

Even then, Fischer needed that call from Kissinger to finally board the plane.

The match itself was pure drama. Fischer didn’t show up for the opening ceremony to determine playing colors. He lost the first game and blamed the television cameras. He refused to play game two, forfeiting it, until tournament organizers moved the match to a private room. Down 0-2 to the World Champion, Fischer’s challenge appeared over before it began.

Then something clicked.

Fischer won game three. And game four. And game five. He began systematically dismantling Spassky’s defenses, games that showcased not just brilliant tactics but a completeness of play that seemed almost inhuman. As one Russian grandmaster described him, Fischer was “an Achilles without an Achilles heel”—a player with no noticeable weaknesses.

On September 1, 1972, after 21 games, Spassky resigned. Fischer took home $156,250 in prize money, while Spassky earned $93,750. But the real prize was bigger than money—Fischer had ended Soviet dominance and become the first American-born World Champion in history.

The Fischer Boom

The impact was immediate and staggering. Membership in the US Chess Federation doubled in 1972, and peaked in 1974; in American chess, these years are commonly referred to as the “Fischer Boom“. Chess clubs sprouted up across America. Children begged their parents for chess sets. Chess books flew off shelves. Fischer appeared on the cover of Life magazine and Sports Illustrated. He went on The Dick Cavett Show and told the world that the greatest pleasure in chess was “when you break his ego.”

More importantly, the money changed. After Fischer-Spassky, the World Championship became a big money affair and has never fallen below half a million in raw unadjusted dollars since. Tournament organizers could no longer get away with shabby conditions and minimal prizes—not when players could point to what Fischer had demanded and received.

Fischer worked on improving at chess like no one else—none of the Russians at the time were true professionals. They all had jobs, degrees. Fischer knew just one thing: how to play chess. He studied 8-12 hours daily, had chess boards in every room of his home, and dedicated himself to the game with a totality that was both his genius and his curse. But in doing so, he showed what was possible when chess was treated not as a side pursuit but as a profession worthy of complete dedication.

The Tragic Epilogue

Here’s where the story takes its darkest turn. In 1975, Fischer was scheduled to defend his title against Soviet challenger Anatoly Karpov. Fischer had demands—he always did. He wanted matches to continue until one player won 10 games, with draws not counting. He wanted unlimited games. And he wanted a 9-9 tie to mean the champion retained the title.

FIDE agreed to the first demand but rejected the others. So Fischer did what he had always done when his demands weren’t met: he refused to play. Fischer lost his world title by forfeit in 1975, and Karpov was crowned World Champion without playing a single game.

Fischer essentially vanished from competitive chess for two decades. When he did resurface in 1992 for a rematch against Spassky in Yugoslavia, the match was played under UN sanctions, making Fischer a fugitive from US law. He spent the rest of his life in exile, his later years marked by paranoid conspiracy theories and disturbing public statements that tarnished his legacy.

Fischer died in Iceland in 2008 at age 64—the same number as the squares on a chessboard. A poetic end for a tragic figure.

The Legacy: Professional Chess Exists Because of Fischer

Walk into any major chess tournament today and look around. Professional lighting. Quality venues. Prize funds that can sustain a career. Top players earning millions. Online chess platforms with hundreds of millions of users. Chess as legitimate sport, not eccentric pastime.

Bobby Fischer made all of that possible.

Thanks to his dazzling career and his demands for better conditions for players, chess was popularized and was converted into a professional activity with many offshoots. His book “My 60 Memorable Games” remains essential reading. His invention of incremental time controls—adding time after each move—is now standard in all top-level play. His Fischer Random Chess (Chess960) offers a variant that removes memorization and returns chess to pure creativity.

But beyond the technical contributions, Fischer did something more fundamental: he proved that chess deserved respect. That the players deserved proper compensation. That the game itself was worthy of being treated as a serious profession, not a gentleman’s hobby or communist propaganda tool.

He did this by being difficult, demanding, uncompromising—and by being so devastatingly good that the world had no choice but to pay attention. Every professional player today owes him a vote of thanks.

The tragedy is that Fischer’s mind—that brilliant, uncompromising, absolute mind—couldn’t survive the peace after the war he’d won. He conquered chess, professionalized the game, inspired generations, and then disappeared into paranoia and exile. He fought so hard for chess to be taken seriously that he destroyed himself in the process.

But the Fischer Effect remains. That’s what we call the transformation of chess from amateur pursuit to professional sport, from shabby venues and pocket change to pristine conditions and life-changing prizes. It happened because one difficult, brilliant, impossible man from Brooklyn decided that chess deserved better—and refused to accept anything less. And you know what? He was right to complain. Because now, more than 50 years after that summer in Reykjavík, professional chess exists in the form we know it.

And it exists because Bobby Fischer, for all his flaws and ultimate tragedy, refused to accept that the game he loved should be treated as anything less than professional.

That’s the Fischer Effect. One man. One chess board. One revolution.

Pingback: Why "Thinking Outside the Box" is a Myth—The Best Moves are Inside the Rules (Chess)